Chasing Rainbows

The term “chasing rainbows” comes from the old tale about finding a crock of gold if one digs at the end of the rainbow, where it touches earth. The idea of chasing rainbows as equivalent to a fruitless quest, pursuing illusionary goals, trying to achieve impossible things.

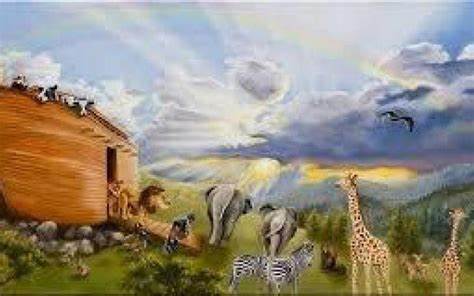

Parshat Noach

One of the signature symbols in Parshat Noach is the rainbow, which G-d displays following the Mabul (Flood) as evidence of his commitment that He will never again destroy the world with water (Noach 9:13). Initially, the rainbow thus appears to be a positive sign – a covenant evidencing G-d’s commitment to mankind.

Rainbows, good or bad sign?

Rashi states that the appearance of a rainbow actually has negative connotations. Observing that the word “dorot” (generations) in the pasuk (9:12) immediately preceding the introduction of the rainbow is missing letters (two “vavs”), Rashi explains that the word “generations” is “written ‘chaser’ (missing letters) since there are generations that do not need this sign G-d won’t destroy the world with water, since they are totally righteous like the generation of Chizkiyahu King of Judah and the generation of Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai. In other words, when a rainbow appears in any generation, it is a sign that there is wickedness in the world, and the generation is deserving of destruction but for G-d’s commitment as evidenced by the rainbow. Indeed, Rabbeinu Yehudah bar Yakar (a teacher of the Ramban) writes in his Peirush HaTefillot Vehaberachot (2:58) that one ought to be inspired to do Teshuvah upon seeing a rainbow.

Why can’t I gaze at a rainbow?

Other sources reflect similar ambivalence concerning a rainbow. On the one hand, one makes a brachah upon seeing a rainbow. But once the brachah is made, it is inappropriate to gaze at the rainbow for a prolonged period of time (Chagiga 16a). This is because the rainbow represents the “Shechina” (Divine Presence) (navi Yechezkel, 1:28), interestingly, there is a natural phenomenon similar to a rainbow called a “glory”. It is also inappropriate to run and tell someone else about a rainbow that one sees since it is like spreading a bad report, the rainbow is a sign that bad deeds are being done, and G-d is withholding punishment (Chayei Adam, 63:4) What can we learn from this ambivalence? What can we learn from rainbows?

The Science behind rainbows

Rabbi Daniel Cohen of Congregation Agudath Shalom shared an interesting observation that perhaps can clarify what we are meant to learn from the phenomenon of a rainbow. Scientifically, a rainbow results when the sun’s rays are refracted by drops of mist or rain into separate bands of color. When we look at regular sunlight we do not see these colors. It is only through the prism of water that the richness of color inherent in sunlight becomes apparent. The rainbow can thus be viewed as a metaphor for enhanced human perception. But perception of what?

Stop and Smell the Roses

In general, during the hustle and bustle of day-to-day life, most people do not reflect on G-d ‘s presence in the world. Various natural events and phenomena occur daily that we tend to take for granted, the sun rises, the sun sets. We ascribe these routines to the laws of nature. What can enhance our perception of G-d’s presence in nature?

Water like Torah

The gemara (Baba Kamma 82a) states that when Bnei Israel went for 3 days without finding water, the allusion is to 3 days without Torah. An absence of water symbolizes an absence of Torah. Shir Hashirim Rabbah (1:19) states that “just as water cleanses the body of impurity, Torah cleanses the soul.” The giver of the Torah, Mosheh, was so named because he was pulled from water. So we see that Torah is equated to water.

Perception

Let us now return to the rainbow. As noted, absent water, we do not perceive the colors within sunlight. Indeed, it may be said that we do not perceive light at all. Every day, sunlight fills the world, and we are its beneficiaries. Yet, light is invisible – you cannot see it – or touch it. It is everywhere, but nowhere. We can generally only perceive sunlight via its impact on the world in terms of being able to see; when it is not present, we cannot see anything at all. But then comes water and makes invisible light visible to all in the form of a rainbow.

Everywhere, but Nowhere

G-d’s presence is like light. Like sunlight, G-d is everywhere. Yet, also like sunlight, G-d is not visible, He cannot be perceived directly by the human senses. Rather, we can only perceive G-d though His impact on the world-if we are willing to acknowledge such. Or by the absence of his presence, resulting in darkness (hester panim).

The Torah

But just as water makes invisible sunlight visible, there is a mechanism that makes G-d “visible”. It is the Torah. We have said that Torah is equated to water. The analogy becomes clear. Just as water enhance the richness of color in sunlight, Torah study is the mechanism by which we can maximize our appreciation of the presence of G-d in life. As water is a prism, so too is the Torah. The prism by which we, more broadly speaking, discover spirituality in a material world.

Rainbows as Reminders

This all suggests that a rainbow is positive. But what about the ambivalence we discussed above? We can recall that certain generations did not need a rainbow. That is because these generations perceived G-d’s presence unaided. They did not need reminders. However, the more common path is for people to take things for granted. Which leads one down a slippery slope to the point where G-d is no longer perceived as a factor in one’s life, and an individual becomes free to decide for himself what is right and what is wrong. Which philosophy, on a societal level, can lead to tremendous wickedness. So the rainbow, displayed through the prism of water, serves as a reminder that mankind is missing the boat, is failing to perceive G-d. Spirituality is lacking. Were everyone righteous operating on a high spiritual, moral level, this reminder would not be necessary. But since G-d is not being perceived, and people are preoccupied with the material world to the exclusion of spirituality, G-d seeks to jolt us into changing our course through the display of the rainbow. The danger, however, is that we miss the message and instead perceive the rainbow as yet another natural marvel. This is the reason that once we make a brachah, which essentially acknowledges the spiritual message of the rainbow, we should not gaze on it any further.

The rainbow is supposed to facilitate renewed recognition of G-d’s presence, but once we have recited the berachah, that purpose is accomplished, and any further gazing may shift our focus from appreciation of G-d’s presence to preoccupation with the natural aspects of the phenomenon. As such, running to tell a friend about a rainbow is also discouraged for this may only exacerbate the problem the rainbow is meant to rectify. That is, as more people gather to admire the rainbow, the focus becomes nature rather than G-d.

The idea of chasing rainbows is equivalent to a fruitless quest, pursuing illusionary goals, trying to achieve impossible things. Instead of chasing rainbows, can we simply remember to remember that when we happen to see a rainbow, to recognize G-d’s presents and the Torah we were given, to enhanced our human perception.

Check out YedidYah “Let There Be Light” a song about The Story of Creation. Music and Lyrics by Rabbi Yakira Yedidia https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H0GEYQYwDI0

Shabbat Shalom